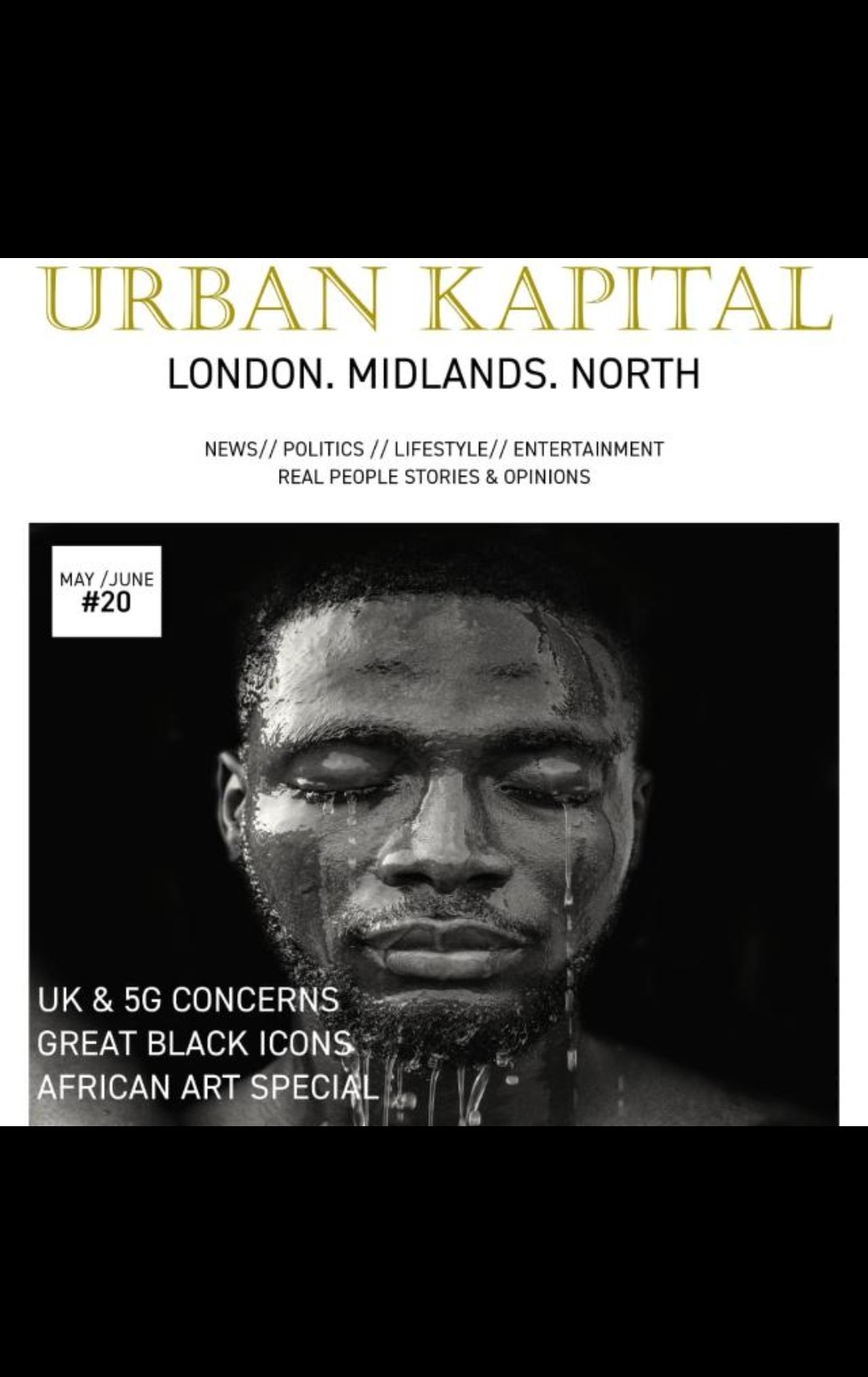

Black lives mattered for some weeks, but now what?

- Urban Kapital

- Jul 19, 2020

- 5 min read

Normal service is resuming. Although some protests are continuing, after three heady weeks of black lives mattering, the news cycle is moving on. It feels a bit like dawn rising on the morning after a large public gathering. The ground is littered with debris, some stragglers loiter here and there, reluctant or too tired to leave, but the street sweepers are already on the scene. Before long there will be no sign that anything happened.

But something brief and unexpected did happen, although already it feels overshadowed by the brawl that followed over the goals and the methods of the Black Lives Matter movement. There was a global revolt by black people – and in solidarity with black people – that spread at an unprecedented speed and scale. The uprising crossed borders and language barriers, as protesters from Paris, London, Brussels and Minneapolis realised their grievances were the same: the erasure of their history, the cruelty of immigration systems, the impunity of the police. Black anger was too strong to contain, and the numbers in the streets were too large to ignore.

We may discover the only thing more detrimental than doing nothing is doing a tiny bit and thinking that's enough.

Was this time different from all the other times before it? There did seem to be some spontaneous alchemy at work: perhaps the long period of lockdown meant that people of all races paid a new kind of attention. They watched George Floyd call out for his mother as his life ebbed away and they watched the US president trample over the pain that followed. They saw the cheapness of black life – and they began to realise that all the excuses they had made in the past for not seeing it would no longer hold.

One way in which this time was not different was the haste to change the subject: couldn’t we talk about something other than statues and empire and history? Wasn’t all this just the distant past? And so, after a few days of protests, black people were once again put on the stand to answer for all this talk about toppling monuments to slave traders, removing old TV programmes out of rotation on streaming services, renaming venerable pancake syrup brands.

Some of this is simply the way our media is set up to host “debates” about whether, indeed, some lives matter more than others. But it is also the way that complaints of racial injustice have always been invalidated. They are turned into matters of opinion, removed from the realm of moral justice and placed in the realm of competing for cultural values. This is how movements for racial equality are easily framed as unprovoked assaults on our cherished culture, which is perpetually under threat of being vandalised by race vigilantes. This is the dog-whistle frequency that was heard by those groups of white men who arrived, without being asked, to “defend” statues across England.

That frequency is amplified by the media’s treatment of race as a spectacle rather than a serious subject, which has contributed so much to the climate of trivialising racism that triggered the Black Lives Matter protests in the first place. The press is not the main story here, but we cannot make progress on racial equality without honestly interrogating and challenging the ways that the public conversation on race has been shaped. If we are going to probe and litigate the complex aftermath of these protests, it cannot be done in the same fashion and on the same platforms that contributed to their eruption.

It is not just the tabloids: from the broadsheets to the BBC, the British press has stoked racism and xenophobia, cynically exploited them for clicks and eyeballs – or hidden behind cowardly equivocation about the sacred right of racists to be heard in weekly columns. And everyone involved is still getting away with it. Editors who happily published Katie Hopkins are today cheerleading for weakness; others are still working with people who think Black Lives Matter has “a racist agenda”, and telling themselves free speech requires nothing less.

Black participants also play a part, feeding the appetite for performative rage by subjecting themselves to the ignorance and sneering of white doubters, only to be thanked with a pat on the head for being so articulate, forbearing it so well, with such grace, for earning a following. Black figures are patronised into sainthood and embraced only when they show dignity under fire, as they are photographed carrying on their backs the injured bodies of their white abusers.

Much of the change accelerated by the past few weeks has been centred on optics – corporations making statements about changes to their boards, brands posting black squares on Instagram. We may discover that the only thing more detrimental to a cause than doing nothing is doing a tiny bit and then thinking that’s enough.

So black people have your solidarity, your concessions that things need to change, your pledges, your retrospective apologies and, in some instances, your resignations. These are gestures, even big gestures, and they do go some way – a long way, in fact – to making some people feel like they belong in a country that will no longer put up statues to those who would have enslaved them.

That is not anything. But the establishment that shapes knowledge and attitudes towards black people remains hostile. The levers that could pull the country towards a deeper reckoning with race are broken or in the hands of those who have no interest in pulling them. The fish of state is rotting from the head down; instead of real change, we will get exercises incorporate face-saving and a (long overdue) scrubbing of public statuary. And black people will end up as an awkward PR pitfall to avoid, rather than a community empowered to shape governments and policies.

For now, black people have their own slightly enlarged clearing in popular culture. Black writers are finally breaking records and on the bestseller lists, and the work of activists is being recognised and presented and profiled and podcasted. But visibility is not the same thing as an influence. Listening to black voices is not the same as listening to black voices only when racism is being debated. This is the curveball to watch out for: we may see a great redistribution of intellectual capital that culminates in another form of segregation, where black people are vested with new credibility, but only on this one topic.

We cannot build on the protests of the past few weeks by falling back on the same structures that precipitated them. And those structures will only change when black people have a real say – not one voiced by white decision-makers or expressed by token diversity hires whose presence is supposed to show the work is all done now. Real change means eliminating the denial of racism, making an honest appraisal of our history, actually dismantling the “hostile environment” immigration policy – and doing all this with black people as leaders, not just cheerleaders. This government is not up to the job – but that’s no excuse for the rest of us. When the protests are no longer on the streets, they should and can carry on everywhere else.

Source: The Guardian, Nesrine Malik

Comments